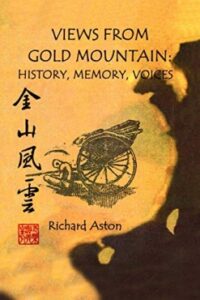

Interview & Conversation w/ Richard Aston, author of Views From Gold Mountain: Voices, History, Memory | March 13, 2022

Introduction. Steve Yip undertook a dialogue/conversation with Richard Aston, the author of Views From Gold Mountain: Voices, History, Memory. In this self-published memoir, Aston unveiled some historical elements of the Chinese Marxist Left (CML) that traces back to Steve Yip’s own family. References to 1000 Wood Street in Oakland is the residence where Steve was raised after his family moved from North Beach to the African American neighborhood of West Oakland. This was after the death of Lawrence Lowe, the driving force behind the CML. The interview below begins after an opening conversation. Much thanks to Antony Wong of the CUNY Asian American/Asian Research Institute, who arranged the platform for this cross-continental dialogue.

STEVE: So when I heard about [your book] from Steve Louie, who I think you said you also know… I began that book last summer [note: 2021], and I had to put it down after a while… it was just so “vast.” My main interest was the question of Henry Tsoi, Lawrence Lowe, Eva Lowe, and that section of the Chinese community that had emerged during the 30s and 40s. It much more piqued my interest when you started naming addresses and locations. And I just said, “Oh my goodness!”

You had 1000 Wood Street, Oakland, California. You know what, that’s where I grew up. Where did you get all this information? This is what we are going to do today. You probably had seen my proposal.

[The book] felt that it was a very atmospheric book. Obviously, it was a labor of love, but I want to get into what compelled you to do this, how long did it take you? And then, I guess, what were you trying to accomplish through it? And you know obviously, maybe some of these questions we haven’t been to consider but you were actually moved by certain things, but also very clear that you had a passion in terms of your relationship with the Chinese community, and in particular in this situation here. Since we’re living in the United States, the Chinese American community. And I like to look at that going forward.

RICHARD: Should I start from the beginning?

STEVE: We’re kind of starting from the beginning! Like I’ll let you go, and I might just start peppering you with questions. I think the main thing is that: Who is the man, what compelled him to do this but I think what? Let’s go back a little bit in terms of you came from United Kingdom…. You’re from Britain, presuming from England. If I can recall, I didn’t annotate your book. So, my recollection tells me that so it’s a very interesting journey.

RICHARD: Okay, actually, I was born in Wales. But when I was young, I grew up in England. This all started quite by accident. When I was 14, I wrote in the book: one day, three Chinese kids arrived at my school. One was exactly the same age as me. One was older when was younger. They didn’t speak a word of English, and I didn’t speak a word of Chinese.

So the headmaster just put his head in the door during time in class, and asked, ‘Do any of you kids know where the Chinese laundry is at?’ So, I said, yes, sir. ‘So, you get out of the class.’So go out to the hallway, and there’s three Chinese boys. There was no Chinese living in the town where I did. These were the first Chinese people I’ve ever met, ever seen, ever met. So he said, ‘Take them back to the Chinese laundry’, which is about a half mile away.

So I get back to the Chinese laundry. Father invites me in, he said, these are his three sons. They were actually born in England. But in 1936, their mother took them back to their village, which is near Toisan. And while they were there, the Japanese invaded, so they were stuck. So, in 1944, they’ve managed to come back to England. Again, they didn’t speak any English, I didn’t speak Chinese. I hated doing math. Chinese kids go to math because English wasn’t required. So they did my math homework, and I did their English homework.

STEVE: A tradeoff.

RICHARD: We became friends for life. The last one died maybe six months ago. And I went back to England frequently. And they visit me in California. So that’s how it all began.

When I was 16 I had the chance to emigrate to America. I know that I was coming to San Francisco, and they gave me a letter of introduction to a relative in Chinatown. When I met this relative, he turned out to be an extremely, friendly gregarious man, with many interests. He ran a grocery store on the corner of Washington and Grant Avenue. So I hang around there a lot. And he started introducing me to many aspects of Chinatown life. He actually found me an apartment on Jackson Street — small apartment right across from the Chinese Hospital.

So I was right in the middle of Chinatown, and through him started meeting a lot of people from various walks of life. He was, in addition to being a groceryman, he had other interests. He was an agent for the Kuomintang…to provide, to purchase materials for them. He was an officer in the Suey Sing Tong. He was a gambler. He was a womanizer. He loved nightlife and drinking. And at 16 years old, he took me on his expeditions — the adventure of a lifetime.

STEVE: This is the grocer you’re talking about most. Was he white or Asian?

RICHARD: Asian. Okay, good Chinese American.

STEVE: And he was a relative of yours?

RICHARD: A distant relative of my friends in England.

STEVE: Oh, I get it now.

RICHARD: So, through him, I made many friends. And eventually, he introduced me to a young Chinese American girl. We fell in love. We got married.. So after arriving in San Francisco. I worked a lot of odd jobs — washing dishes, cooking in a restaurant. And finally managed to get into the Merchant Marine. So I made quite a few trips to the Far East.

STEVE: How old were you then?

RICHARD: I would have been 18-19… So, in 1950, the end of ‘52, something like that, this friend of the friend of mine is… his name was Bill Hing. He took me to the picnic of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, which is a very big organization in Chinatown, still exists… At this picnic, I met a young girl, Chinese American girl. And that started a whole different part of my life.

STEVE: After a while, she said that your marriage can’t continue if you keep going to sea, that you gotta get some kind of job.

RICHARD: Well, I never finished high school. So she said go to San Francisco State, they take anybody. And so I went to San Francisco State, took the entrance exam, and managed to pass it. Coincidentally, that very first semester, they offered the first Chinese language program. [The] instructor’s [phonetic: ‘tie your shoe’], who’s been an officer in the Chinese Air Force. Moved to America, and now he’s teaching. So I said, why not take Chinese. I know a bit of Cantonese already, but this was a formal class. So, I took Chinese. And after four years, I got a degree in international relations with a minor in Chinese.

STEVE: So you went through a very interesting journey and, which is why I’m trying, to like one thing I pointed out in my note to you, is that I was trying to get a composite picture of who the man was, Richard Aston… And then, was that after or before you went to the Merchant arine.

RICHARD: No, it was after. I’d already been going to sea for a couple of years before that… And because that in the 1950s, the United States didn’t recognize China, didn’t recognize Red China. But when I was sailing, I had a British seaman’s passport. And so when I went to Hong Kong, I could actually cross the border into China. So my first visit to China was in 1953, somewhere around there, only a short time. But, and then since then, I’ve been back many, many times.

STEVE: So we can transition a little bit. I think we established basically how you got to where you’re at. And then at one point, you actually worked for the US government, it seems like.

RICHARD: Well, after I graduated from San Francisco State, the American government opened up a place called the East-West Center in Hawaii, which was a research center where they brought scholars from all over Asia. And they thought by putting them all together with Americans in the middle of the Pacific, they could learn a lot from each other.

That was the start of maybe a six-year journey. Where, from the State Department, and from the Defense Department, I was appointed a national defense scholar, which allowed me to travel all over Asia, interviewing people and doing research on different topics… So, during these six years, I visited almost every country in Asia. I had an airline pass good for any airline, anytime, anywhere in Asia. So I was hop skipping around from place to place.

H. Mark Lai, Mun Ching, and the ‘Chinese Marxist Left’

STEVE: So, you did that for six years. And then, if I can remember… maybe we just do some jumping around, and then instead of going chronologically… I was most fascinated by your introduction, with people whom Him Mark Lai called the “Chinese Marxist Left”.

Before we go there, when did you start to, when do you start to decide, thinking about doing this book? And what was the compelling reason behind it? Obviously, there was a lot of things that confronted you to do this monumental work. I mean, it’s monumental — 700 pages. You know, so what’s the story there, sir?

RICHARD: Well, just over many, many years, I collected notes and essays that I’d written, and travel memories and diaries and all. And then when I retired, I figured, ‘Put it into a book!’ So it started, It was simply like the memoirs of Chinatown. But then it took on a life of its own and grew and grew and grew into the monster it became.

STEVE: So how many years was that?

RICHARD: It took me at least three years I would think. That’s when I quit working. So, do you want to start with how I knew Mark Lai?

STEVE: Yeah, let’s move into H. Mark Lai [which bridges] into the question of Henry Tsoi and Lawrence Lowe. And as I explained in my various emails, Lawrence Lowe basically was my father’s mentor. And after he had passed, my father took possession of his grocery store — West End Grocery [in West Oakland]. And at that time, I was probably in the sixth grade [in San Francisco]. Yeah, I was in sixth grade and we moved from North Beach over to West Oakland. So that was a big cultural transition for me. Coming from a more Chinese-dominated culture in North Beach, and then all of sudden you’re in the middle of the Black ghetto. And cultural collisions, of course, ensued. But also, I think I learned a lot in that kind of situation. But please, tell us how that transition came about.

We can start with Mark Lai. And also just for your information, Mark Lai delivered the Chinese language [Cantonese] eulogy for my father when he passed in 1998. So, his family and my family are relatively close.

RICHARD: Okay, so, I think in 1959, my wife was working at PG&E. And she and Mark’s wife, Laura, were the first non-white people to be hired by PG&E. So they were working at PG&E. At the same time, Mark was working right across the street at Bechtel Engineering. So after work, Mark and Laura, me and my wife, would walk up to Chinatown to Jackson Cafe for dinner… We get soup. Three dishes over rice, and tea, over $5. And we went there very frequently. So that was the initial meeting.

Okay, late in the year 1959. A house came for sale up on Union Street, small house. Both Mark Lai and his wife, and me and my wife, were interested in buying it. So we went up to visit the house and Mark said he wanted to buy it. So shortly, he bought it.

At the same time, Mun Ching had to close down. It had been investigated by the FBI. The FBI raided it, burglarized the place, got all the membership records, and were preparing to list it as a subversive organization. And they were preparing to arrest members of, I think, if I’m right, one member was actually arrested and convicted of subversive activities. So the others sort of dissipated before that.

So, in 1959, Mun Ching was closed down. It had a big library. So Mark’s new house. They couldn’t take all the books: all the English books Mark gave to me. And he took the Chinese books to the house on Union Street. At the same time, Mark dissolves Mun Ching. But started a new organization called [Hoi Yin 海燕].

STEVE: Yeah, I can’t remember the Cantonese, but it sounds very similar.

RICHARD: [Hoi Yin] is a bird – stormy petrel. According to legend, it never rests. It sails [the] stormiest seas and never rests. And Maxine Gorky wrote a book about that, which became very famous in China and in Russia. So that’s where Mark got the name from. This homeless bird that never rests. So and so he tried to try to maintain that organization as best he could that way. But again, this was a time when the Un-American Activities Committee was investigating everybody.

And slowly, the members just frittered away. I mean it was just impossible to maintain the membership under the pressure at that time. I sent you a copy of their loyalty oath. Yeah, there were so many questions on there. The people who were in Mun Ching, for example, couldn’t answer them without getting into difficulty. And so the membership just frittered down to nothing.

STEVE: I actually remember that library myself. It was there when we were younger [and] during the Vietnam War, we would have vehement debates among the offspring[s] about the right and wrong of the Vietnam War. Go ahead, sir. What were you do it professionally at this time?

RICHARD: That time mostly going to San Francisco State, working at PG&E at night. Just for those four years. So, Mark and Laura, [we] became very friendly. So, at the end of his life, just a few weeks before he died, he came to my house and had dinner, with Laura. And then I came straight out and asked him: “Were you ever a member of the Communist Party?” And he said, “No.” And I’ll explain why. So many people. He said, “I was being groomed to join the Communist Party, but I never did because of the loyalty oath.”

Because of the loyalty oath, the Communist Party decided not to register any more members, so that people could not be accused of being subversive. So everybody knew who would be a communist, but they would never officially be ‘communist’. And he fell into that category. So, he was a communist in his spirit, but at least not legally.

And again, I was friendly with him. I was friendly with Laura Lai. She died like two years ago, I had lunch with her like a week before she died. We stayed friends for that long.

STEVE: My sister Shannon was about to sit down with Laura just before she passed. And that was after Mark had published that autobiography he had. And my sister was trying to get hold of Laura… Yeah, that was a great loss, it was kind of shocking, so quickly after Mark had passed.

RICHARD: You know she was so vibrant right and up until the end, full of life, you know, every time I go… Every other week: “Let’s go for lunch, out for dim sum.”

STEVE: She loves driving. So, were you aware of Mun Ching when you guys were socializing after work?

RICHARD: Very much so. There’s another aspect now to my knowledge of Chinatown. My wife had a friend, and we became very friendly. So, she came from a large family. And one of them, her eldest sister married the son of [Choy Suht Chiu], [Choy Suht Chiu] was the oldest of three brothers. The second one was [Choy Char-ming]/[Choy Fa-Joe], which was Henry Tsoi. The third brother was [Choy Chungming], who was Lawrence Lowe.

STEVE: We use to refer to Henry Tsoi as [phonetic: Yee Bak Fu].

RICHARD: So, because her elder sister was married to the son of the eldest Choy, the Choy brothers. We became, she became very family. So she, she got to know Eva very well, she got the note.

Helen, my second wife, her sister was a cashier at World Theater. My wife babysat Henry Tsoi’s youngest daughter, Cynthia. And was friendly with Henry Tsoi’s oldest girl, Lillian. So that’s how I came to know Henry Tsoi and [Choy Suht Chiu], Henry Tsoi and Lawrence Lowe. Lawrence, I never met.

But, Eva, we met frequently. Once again, up until almost the day she died, we were over to her apartment on Powell Street. I was there… I think you mentioned that you were at the 99th birthday celebration at the Imperial Palace.

STEVE: Yes, 99th birthday, right, I was there.

RICHARD: So we were there at the same time.

STEVE: Was this when you said you were going to San Francisco State, and you’re working at PG&E at night?

RICHARD: This came later, after I’d come back from the Far East.

STEVE: So this is after you finish your little stint with the State Department.

RICHARD: Well, no, because when I came back towards the end, I was enrolled at UC. In addition, in the Ph.D. program, which meant I didn’t wasn’t taking classes. I was just working on my dissertation, which meant I could take off for, go to the Far East for a month to do some research, and then come back.

And then during those trips back to China, that’s when I met Henry Tsoi at the China Travel Service. And sometimes I go with my wife, sometimes alone. But then he would arrange for us to go into China. I’ve been to the Choy family home in China several times when Henry and his brothers grew up.

And so, again, I must have seen him… just last summer saw Henry Tsoi maybe a year before he died. A couple of years earlier he came over to the United States for a visit. And I met him then, and then Lillian came over for a visit, then Cynthia came over to live. I saw Cynthia last, maybe a year ago. So, my second wife was very friendly with the whole family.

Rejecting the Loyalty Oath

STEVE: All this time, and you’re making visits to China. Did you perceive it to be a conflict that you had a certain relationship, an employment relationship with the State Department or doing research, or is what you’re doing for your Ph.D work?

RICHARD: Working… My political views.

STEVE: That was where I was trying to get at. Then, how do you feel about that?

RICHARD: My political views didn’t have anything to do with what I wrote. I could write objectively about conditions in various Chinese communities. Like visiting Chinese communities all over Southeast Asia, and made assessments of their attitudes and living standards and such. So, there was really no conflict.

The only time that conflict came up was in 1969, when suddenly, you know where Sproul Hall is on UC campus? …Sproul Hall was where every month I went to pick up my check from the government. So I went there one day and what ‘69 or something. And they said, “You haven’t signed the loyalty oath.” I said,“So what’s that?” “Oh, this is something new” So they gave me the list of questions, and answer these. Well, there’s no way I could answer them without getting into problems. So that ended my stint at UC. I just had to drop everything and forget about a Ph.D.

STEVE: Wow, which actually… now that that issue’s being brought up. How did you perceive, and you talked about Mun Ching having to close down through that era?

Because I knew there was a lot of pressure on a lot of people, and couple of people like you said, were arrested. One person was convicted. I know, maybe possibly one or two were deported… I do remember one time the FBI came by and knocked on the door, and this and that, and that and this. So, even as a youngster, I knew something was up. How did you perceive that particular situation, in terms of how it impacted on people that you knew on a very personal level?

RICHARD: There was a major division with those Chinese Americans who felt some affinity for Communist China. They thought that by going back they could help reconstruct the country, and their expertise in various fields was of value.

There were others who were more secure in their ties with America, you know — grandparents, grandchildren, who thought, well, we can stick it out here. And so there was a whole range of attitudes. I mean there was, there were some Chinese Americans who were very much in favor of the Kuomintang.

So you had the whole, whole range of a number of speakers that would come to Chinatown — Kuomintang generals, middle of the road generals, and almost-communists, were quite a few communists that were… came as part of the end of the war, the treaty that took place at he Opera House, I forget the one… The United Nations Conference.

STEVE: Did you perceive the stress level among those people that you’re already being associated with like Mark and Laura, because it was a very, very tense period. It was also the McCarthy era. For example, people like my father, for many years could not leave the country. He actually was a paper son, as I discovered later on. And so, for them to even step out would actually be a big risk of not even coming back into the border. I just want to know how people survived that kind of stress? They were under death threats from the Kuomintang as well as from the Chinese Six Companies.

RICHARD: And then with the loyalty oath thing. People who took it, and then charged with lying on it, or again, potentially paper sons who were arrested, not arrested but interrogated and said, you know: Give up three other people so you can stay… And I know some people worked at [the Bechtel Group, later the Bechtel Corporation]. Because Bechtel worked on government projects, there are a number of them that could sign the loyalty and they would quit and be forced to leave. So the whole 50s and 60s was a very tough time fraught with anxiety amongst many, many Chinese Americans.

STEVE: Did you feel yourself in danger of being demonized, or even accused of being associated with people who were being targeted are mostly from the Left?

RICHARD: It was the whole society… like the longshoreman’s union… I was in the longshoremen’s union. Dozens of those were put out of work because they couldn’t sign the loyalty oath… people who worked for the post office were in the same position.

STEVE: So it wasn’t just a Chinese community.

RICHARD: It was literally thousands of people all over America, as I mentioned in the book. Would you believe, Tennessee passed the death sentence for anybody found with a piece of Marxist literature. That was the depth to which this paranoia would [??] in America.

STEVE: Yeah. It’s kind of going that way right now. It’s we’re moving into very dangerous territory right now politically as we’re looking at it. So, are you done with this particular session you have any other thoughts, because I want to at least transition that to something that’s related more with you.

A lot of ingredients you actually surfaced in this book. And it was kind of mind-blowing for me, because you can get some generalities reading Mark’s [materials]. He wrote at least one to three pieces about Mun Ching and the Chinese Marxist Left, but he wouldn’t go beyond certain parameters. I remember one time when my daughter was in college, she called him up and tried to talk to him about it. He wouldn’t talk. And it’s sort of like ‘go read my articles.’

Basically, but you went much deeper. How was that achieved and how comfortable were people? …You are talking with Eva Lowe. And that you’ve got permission to actually surface this information. Can you verify that and also tell us more about that?

RICHARD: There were limits to what Eva, for example, would talk about. She was very… Eva herself was very hesitant to talk about anything political. Even though through other sources, I knew that she had participated as an active member in communist activities while she was in China. And then, particularly when she was in Manila, putting out a newspaper for the Chinese Communist Party. But she refused to talk about that.

STEVE: But you somehow, then how did that information surface?

RICHARD: Actually, the thing about the newspaper, I found out, by a woman who wrote a letter to Mark Lai. And it’s in Mark Lai’s file at UC.

Personages of the CML: Ben Fee, Lawrence Lowe, Henry Tsoi

[Note: We discussed certain social issues within this movement that involved the activist Ben Fee, who was president of the Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association and leader of the Chinese section of the CPUSA.]

STEVE: Ben Fee, did he move to Los Angeles?

RICHARD: He moved to New York. There are three Chinese that I know of… Okay, the communist party of any nation maintains if a communist moves from another country, like a communist who comes from another country, to America, they must join the American Communist Party. The Chinese didn’t want to do that. So they were allowed to set up what was called the Chinese Fraction. And over a period of time the head of the Chinese Fraction was Benjamin Fee, who in the 1930s had gone to the Soviet Union for training. Then come back to America, and had…

Ben was one of the heads of this Chinese Fraction there was another one before I can’t remember. The second head of the Chinese Fraction was Henry Tsoi. The third head of the Chinese Fraction was Lawrence Lowe. So there is no doubt about it, that they were high up in the Communist Party.

And then… some of this is from Henry Tsoi’s biography. I tried translating it and I actually had to give up, and have somebody help me with it. And it was… he was quite forthright in his acknowledgment of the road he’d taken.

STEVE: Yeah, my sister sent a page of this bio; she stopped cuz she’s an ABC so she wasn’t able to understand most of it. I reiterate that those names constantly come up in our family discussions: Henry Tsoi, Lawrence Lowe, and all these people… trying to connect all the dots constantly. So was the Lowe family aware of your assembling of this information and putting it into print?

RICHARD: No. I never met Lawrence before he died because he was, ‘shall we say’ murdered?’

STEVE: This was in a car accident on the Bay Bridge.

RICHARD: Henry Tsoi never talked politics when I was with him. In that day and age, it was something you didn’t talk about openly, considering the atmosphere. And then, with the paper sons things, it became deeply forbidden territory. Even though you knew that these people were not the family name they claimed to be. A lot of this was you could only tell with really intimate friends, like with my wife’s family. Within the family group, they would discuss all this stuff. Again, with Eva, up to a point. Once again, it usually wasn’t me asking the questions. It was, I would ask my wife, asked this question. Coming from her, it was more acceptable.

STEVE: So I get it. But the details of some of your expositions of meetings with high-level people [Note: of the Chinese liberation struggle] at 1000 Wood Street in Oakland, California, sort of knocked the socks off me. Oh my goodness! Even the fact that Lawrence Lowe took out ads for various causes and listed 1000 Wood Street in Oakland as a contact. How were you able to get that information to verify that?

RICHARD: You’re just talking with people. Say, the Wood Street grocery was part of a number of supermarkets that they owned up to Northern California.

STEVE: They being whom? The Chinese communists?

RICHARD: Henry Tsoi was involved.

STEVE: So he basically gave you a pass on it. I’m telling you, you can tell by the nature of my questions — how did this come to pass? I think it’s a great contribution. Not just interesting to me on a personal level, but I thought it was some digging very deeply to understand certai

STEVE: I got that sense…

RICHARD: Lawrence was one. And there’s a name that I know is [phonetic: Shiu Tai-wai]. He was an accountant.

STEVE: And he was the bankroller? He was the banker?

RICHARD: He was a central figure in the money. Somehow or other… He was the accountant for this whole group, and he is kind of a shadowy figure. The only thing I know about him otherwise was he wrote a Chinese American dictionary.

Because after Henry Tsoi went back to Hong Kong in about 1951, about then. This [Shiu Tai-wai] was already, was still, still sending Henry Tsoi’s portion of the profits back to Henry Tsoi in Hong Kong. One of these, one of these accounts, he mentioned other members of the party will receive theirs. So it was an intriguing statement that I’ve never been able to pursue, but apparently, there were other members of the Communist Party who had interest in these markets. And in the book, I mentioned a chicken farm up in Petaluma somewhere.

STEVE: That is wild!

RICHARD: Like nobody can tell me who financed the World Theater.

STEVE: That was my next question.

RICHARD: One of the guys involved was with the first husband of Mao Zedong’s third wife. Like I’d have to look his name up, but there were a couple of Chinese film stars, film directors, who were involved in the World Theater.

STEVE: And I was talking to someone else as many years ago — he was SDS’s national secretary 1965-1966. And he told me that the Soviet Union was bankrolling a lot of these movie theaters in the United States. So I was wondering whether that money came from Russia, as opposed to you know sources associated with the Chinese Communist Party.

RICHARD: I would suspect not. The Russians and the Chinese were never as close as they should have been or expected to be. There were some connections like the tickets for World Theater shows were on sale at the Russian Institute on Sutter Street or wherever. And then there was the American labor school. Again, which was a meeting place for communists of all stripes. So, there was individual contact. But contact between different groups, but I don’t think any high-level cooperation.

STEVE: Was there any ties between this grouping of people, influencers, with China Books & Periodicals?

RICHARD: Oasis Bookshop?

STEVE: No, Oasis Books was the one in Chinatown. China Books & Periodicals actually imported stuff from Mainland China. Henry Noyes and his family?

RICHARD: I don’t know. But then the other Maritime Bookstore, which was a meeting place for left-wing people that Henry Tsoi and Lawrence Lowe often frequented to negotiate with their American counterparts.

STEVE: A lot of going on. Were people are aware of you writing so deeply about Henry Tsoi, Lawrence Lowe, and the whole Mun Ching milieu. Did you receive any resistance or pushback from that?

RICHARD: No, because half of them by the time I started writing, most have been dead and buried already like Mark Lai, Lawrence Lowe, Henry Tsoi, even Eva. It was until after Eva died as I started writing this. I mean, I’ve been thinking about it for quite some time, but never kind of coalesced.

STEVE: Did you have contact with the son, Dr. Rolland Lowe?

RICHARD: Yeah… not long before Rolland died, he invited me to a party and thanked me for the book, and that is a photograph taken. [Holding it up.]

RICHARD: It was just pure accident that all these different aspects of my life happened to come together just when meeting [in the UK] three Chinese kids back when are they were young, that my interest was sparked, then that to meeting other people, marriages and travels and…

STEVE: Okay, so we were recounting [about] Lawrence Lowe, Eva Lowe. Lot of people have passed. You had spoken with Dr. Lowe. He basically gave you a thumbs up in terms of your publishing the book. So here’s the question: What kind of reception have you received in terms of the publication of the book, not just among the Chinese people but in general?

RICHARD: Disappointed. Most people will find its too big and too heavy to read I guess. There’s very few comments about it.

STEVE: I bet if you recall, I had to put the book down for a couple of months during the summer. I had to read something else for the time being! But I jumped around in the book because I went directly, almost very early on, to the part about Henry Tsoi, and Lawrence Lowe…

Last point: You have a great passion throughout the book. In terms of the trials and tribulations of Chinese people in China, but also in the diaspora. And so, I thought that would be a seemingly stupid question, but would that be an accurate question in terms of your travels, your involvement, and your participation in the Chinese American community in the United States?

It’s passionate in how you draw the different links, both in terms of this subjugation of the Chinese nation, its resistance, and how that passed into how people saw themselves as they moved into the diaspora. It certainly had a big impact on how I perceive things as a Chinese American… Anyway, any last words and thoughts in terms of your whole travel within the Chinese diaspora?

RICHARD: Well, it is not ended. In normal times before this COVID thing, I go to China every year… And the Overseas Chinese experience is something that the Chinese think about. But there are just two years ago, they opened up a new Chinese Overseas Chinese Museum in Beijing, which again, brings up a lot of things about the coolie trade and all that. So it’s a topic that’s of interest in China also.

RICHARD: Yeah. I hope to see you. I have a stack of photographs of people in Chinatown that I can’t give names so I’m hoping that you will recognize some of these.

STEVE: I can share them with my sister. Is Maurice Chuck still alive?

RICHARD: I don’t know. Is George Woo still alive?

STEVE: George is still alive. George, as you may know, is my aunt’s brother-in-law. [See the interview with George Woo elsewhere in this section.]

RICHARD: I met him just once. We’re organizing some kind of demonstration and we met in the basement of [a] publishing company on Clay Street.

STEVE: Was it called: FUCKU? I wasn’t trying to be profane, but that was the acronym — Free University for Chinatown Kids Unincorporated.

RICHARD: Yeah.

-end-