Part One: Making Bilingual Education a Reality in Oakland, California, Public Schools

Introduction. Shannon is a multi-generational Chinese American. Born in San Francisco, she attended Oakland Senior High School and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley. Brought up in the ‘50s/’60s within a community of Chinese immigrants supporting a democratic society in China, her father was a paper son who emigrated to the United States in the 1940s; her mother’s family began their U.S. roots in Arizona. In the period of WW2 and after, her parents followed the civil war and the anti-Japanese war waging in China and were influenced by the Chinese liberation struggle toward a democratic China in the 40’s and 50’s.

Shannon grew up in this influence of change for a better society and became an educator with a fervent focus on bilingual education confronting the barriers and struggles to educate all children in the United States. She is also a Chinese folk dance learner and practitioner and has dedicated her life to introducing diverse Chinese folk traditions and cultures to generations of younger people. As the program director of the dance organization, Chinese Folk Dance Association, she helped to expose dance students to other cultural communities while promoting Chinese cultural diversity. Shannon is also a former member of the Board of Directors of the Chinese Cultural Center of San Francisco, promoting arts of all mediums.

— Steve Yip, New York, July 25, 2024

Summary In this interview, Shannon Yip shared her journey as a retired educator and passionate advocate for bilingual/bicultural education. This interview held in May 2023 was intended to begin with her association with the Chinese Folk Dance Association, an offshoot of Mun Ching (the Chinese American Democratic Youth League), a progressive literary and cultural organization during the late ‘40s and ‘50s. However, this prequel focused on Shannon’s passion for bilingual education, where she expounded on the challenges and opportunities as an educator lofting bilingual education in the Oakland (CA) Unified School District.

Shannon highlighted the difficulties in teaching Cantonese and Mandarin to students from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds and the need for equal opportunities in education. Additionally, Shannon contextualized the importance of addressing cross-cultural dynamics in the classroom and validating students’ cultures and languages in a multicultural society. This interview was done by Steve Yip, with subsequent edits by himself, Koyuki Yip, and Shannon herself who has added contextual commentary.

Part 2 of this interview will focus on Shannon’s activities with the Chinese Folk Dance Association of San Francisco.

Steve: Hi, let’s start with who you are. Tell us about yourself.

Shannon: My name is Shannon Yip. Who am I? What do I do today? I’m a retired educator, what does that mean? Means that I taught in the Oakland Unified School District for 30-something years, can’t remember how many — 35 years. I started as an instructional assistant in the school system and ended up going through the ranks from being a substitute teacher, classroom teacher, and a teacher who taught other teachers. I ended my career as an assistant principal and as a principal for many years – for a total of maybe 14 years.

I led my school in the implementation of ESL [English as a Second Language] and conducted an instructional ESL strategy, called the Sheltered English approach[1]. My school had, for a few years, at least 18 languages, to which I had only 3 to 4 students who actually spoke ‘Standardized English’. The dominant languages were ‘Ebonics’, Chinese, Spanish, and Vietnamese. As for the Chinese languages, there were Cantonese, Toisanese, Mandarin, Zhongsanese, and Chew Jow.

During that period of time, I was — on every Saturday — involved with Chinese folk dancing in San Francisco at the Chinese Recreation Center on Washington and Mason Street. It has since been renamed the Betty Ann Ong Recreation Center.

Steve: Before we jump into the Chinese Folk Dance Association, could you just elaborate a little bit more about your educational experience? What schools were you the principal and assistant principal at? And I understand you were also a bilingual teacher. Is that correct?

Shannon: That is correct. I started my career in bilingual education. I believe in the bilingual/bicultural approaches. I received my BA at UC Berkeley and returned to obtain my bilingual education teaching credentials. UC Berkeley was one of the first bilingual teacher programs. I wasn’t involved in the first year of this program, but I was in its second year there. Bilingual education was one of the programs used to work with immigrant students in learning academics in the school system as well as in learning English. I received my master’s and administrative credential in education at Cal State Hayward, now Cal State University, East Bay.

Later, after several years as a classroom teacher, I became a teacher-on-special-assignment, who conducted bilingual teacher training workshops, and workshops for other teachers and administrators, as part of instructional staff development in utilizing bilingual strategies to teach English as a Second Language (ESL), multicultural infusion, and cross-culturalism.

There was an interesting aspect in this because the challenge for me was that Cantonese — being an oral language versus being a written language — to which a lot of American-borns (American-born Chinese, ”ABCs”) did not initially speak Cantonese. A lot of American-borns’ home language when we/they first learned to speak was one of many country-side dialects of China. A lot of ABCs spoke the country-side dialects, which could be Toison, Hoiping, or Zhongshan.

Our parents either spoke Hoiping or Toison. We were fortunate enough that my father had the foresight to teach us Cantonese. We were going to Chinese school when we were younger before we moved over to Oakland. Because Cantonese at that time was the communicative language between the different country [rural] dialects of China. BaBa said learning Cantonese provided a bridge between the city of Canton, which spoke Cantonese (of course) and the country-side villagers who spoke various country-side dialects. So being a bilingual teacher was hard because we had to also learn the formal standard oral Cantonese and standard written Chinese, which is different from oral Cantonese. With the addition of Toisanese not being a formal language number one, number two — it had a lot of slang different from Cantonese, and number three it wasn’t a written language. So that was a challenge for our bilingual education at the beginning of its formation.

So we had our own conflicts; because we were challenged by people coming over from Hong Kong, who thought that because they were native Cantonese speakers and had the Chinese language they could seek an easy job and teach bilingual education. That thinking became a challenge and kind of put a red flag over bilingualism because if you don’t have a good system, and good people in it, the system doesn’t work. It doesn’t matter how much you work.

Unfortunately, many of these native Chinese bilingual teachers were handicapped because their English was incomprehensible to the non-Chinese students, taught as they would back in China or Hong Kong, with expectations from the feudal days of teaching and learning. They couldn’t teach according to the needs of the students, as associated with American society and culture. Consequently, their participation in bilingual education revealed the need for professional standards for bilingual/bicultural education. Thank goodness, though, along came native Cantonese speakers who taught with strategies and understandings appropriate to students in this society.

My first classroom experience was supposed to be on a Chinese bilingual track, but I found myself in a classroom with Asian immigrants of many ethnic backgrounds; and only one student was part Chinese. I learned to work in an environment teaching students the general curriculum with English as a Second language approach, while they are learning how to deal with US society; with an administration who didn’t really understand bilingual teaching concepts. As far as the administration was concerned, all Asians were lumped together. And there wasn’t even an understanding of the different Chinese language and cultural groups. For example, all the kindergarten and 1st-grade Asian immigrant students were placed in my combined-grade classroom.

So it got to a point where I had to learn a lot of Cantonese, teach bilingually, and teach what’s called Sheltered English strategy[2] as well as, learning what it means to teach cross-culturally. That also became part of the challenge of the school system at that time. And in fact, for me, it helped me become a better principal, a better administrator. I ended up as a principal at this elementary school — a Flatlands school that had a lot of low-income kids which was 50% African American. The next largest number was from the Spanish-speaking community, the next group was the Chinese representing three different dialects, and finally the Vietnamese population. With the Chinese population, I ended up with three different dialects. I had Toisanese and Cantonese from Hong Kong and Mandarin from mainland China or Taiwan. I also had Mongolian, Italian, East Indian dialects, and Lao, and Mien languages as well. The school already had the challenges of hosting different cultures.

Steve: Oh, I see. So basically the Oakland Unified School District began to recognize the need for bilingual-bicultural education very early.

Shannon: Very early, I think the Bay Area overall recognized the necessity. It was an emergent need stemming from the federal law from the decision Lau vs. Nichols[3]. Yeah, that San Francisco was cited [by this decision, ed.] where students were not provided equal opportunity in education. So due to that lawsuit, bilingual education came out strong.

Steve: Okay, what year and what timeframe is this?

Shannon: Okay, this is soon after my college year and I think 1976 or 1978. It was very interesting. It was very challenging at the same time. Because you have to deal with all the different cultures working to teach them English. You have to teach them societal dynamics and how to blend in. Another challenge, especially amongst South Asians, was those who immigrated with money and higher social standing. They were from highly stratified societies, and how they treated you as a female educator was very different.

Steve: Do you mean the parents?

Shannon: The parents but you can tell it trickles down to the students but yeah, the parents. The parents made sure that their children got their education. There were disagreements over approach, how our school way of doing things was not the way they expected. Which is similar and ironic because it’s similar to how we grew up. When we first went to school being American-born Chinese, we went into American school, not knowing any English. That’s very similar.

Steve: How’s that similar?

Shannon: Well, we first attended school as non-English speakers – I went to kindergarten not knowing any English. So it’s similar to a lot of students that I had when they came into their American school — not knowing English.

Steve: Yeah, same here.

Shannon: Right, and so it is similar to a lot of students that I had. They came into American schools not knowing any English. And the difference is that there were fewer of us [Chinese] in school, so we adapted, acquired, and adapted English quicker. However, at Washington Irving Elementary School in San Francisco, the population seemed to be either Chinese or Italian. And with the differences at that time, the teachers’ attitude toward us was different. They forced us to learn English and they made us feel like, you know, you‘re nothing unless you fully learned correct English.

Steve: Yeah, that’s true.

Shannon Right. Before I became an administrator, I was a classroom teacher. We wanted to give our students validity so they didn’t feel like they’re non-achievers. They’re “failing” just because they don’t speak English. So a lot of bilingual teachers who entered this field came with that mindset that we want to provide validity to your culture, to your language, and help guide you along — to acquire English and learn social habits. I think we did a pretty good job of it, but we were definitely challenged as far as our own bilingualism. As American-born Chinese, our families spoke either Toisan, or Zhongsan, and not necessarily Cantonese. And so that was a challenge during that period in time.

Steve: Okay, that’s interesting.

Shannon: Yeah. So, I found that the confidence level among different students is very, very different. Because of the way their native language sounds, and because Spanish is also Latin-based. Non-Asian students acquiring English was a lot easier in terms of sentence pattern, in terms of tonation, in terms of accents compared to a lot of kids from Cantonese-based speakers, who spoke various Chinese dialects. We also had a hard time because we had to convert our accents; we had to reverse our sentence structure in order to speak standard English.

Steve: I presume there was a lot of background work in the administration of the school system to provide support for bilingual teachers like you?

Shannon: Yes, I actually became part of that support system.

Steve: I see.

Shannon: So I’m a classroom teacher, But when I left the classroom, I went into the bilingual education office. I was recommended to go, and I became a Staff Development Teacher. And what that means is that I provided support on how to teach bilingually; how to teach social and cultural infusion.

For example, classroom management. You flick the light and you get the students’ attention without having to scream. Some teachers turn off the lights and on. The students know right away that they have to face the teacher and/or they put their pencils down. So that’s standard classroom management. Instead of flicking the light off and on, some teachers use the stylophone. I will bring out Chinese symbols or bring up the Chinese drum or something that’s culturally Chinese, like the flute or something like that. And I instruct the teachers how you bring cultural infusion into the classroom with a similar pace.

For example, in first grade, we teach simple science topics, like food. You have four food groups — the curriculum has all ‘American’ food. So there is no such thing as bok choy or siu choy. So I start teaching like, ‘Hey, what do you eat every day? Do you eat tofu? Do you eat bok choy, you eat siu choy, you eat gai lan?’ So I infused that part into the food group class so the Chinese kids will feel validated. For my African-American students, I brought in mustard or collard greens as an example; for mustard or collard greens aren’t one of the highlighted vegetables found in the curriculum.

Steve: Yeah.

Shannon: And so “ that’s what I eat.” And then you have a conversation in the classroom with the Black and Chinese children and they notice, “Well Chinese mustard, Chinese mustard looks similar to mustard greens”. Yeah. And so when you bring that in, they go, “We eat that.” Well it just so happens to be Chinese. And they go “They look the same.” And then you go, “Oh good. We have something in common.”

So they feel validated when you promote commonality. Then of course, for example, we did perceptual motor skills in the classroom. I don’t know if you remember where we used to connect the dots.

Steve: Yeah, okay.

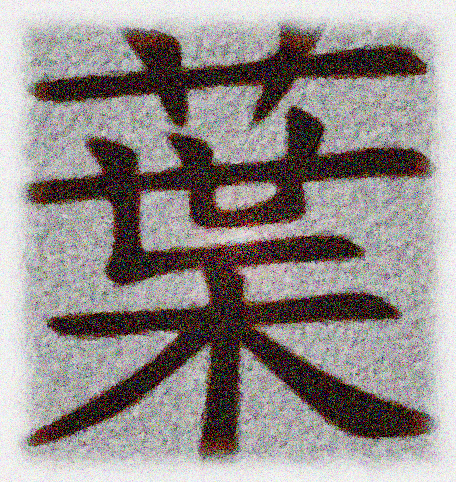

Shannon: Okay. So along that same thinking, I will teach the teachers, “Okay, let’s notice that difference. In Kindergarten, and sometimes in first grade, students must learn the difference between the shape of a /b/, /d/, or /p/, /q/. I would show the Chinese character for big (大) and the character for too much (太). Find the difference.

Steve: What kind of teachers did you train?

Shannon: Bilingual teachers. Chinese, Vietnamese, and Spanish-language speaking teachers.

Steve: Bilingual teachers both in Chinese language and in Spanish language.

Shannon: My area wasn’t just Chinese for Chinese teachers. I have a parallel partner who does it in Spanish and a third parallel partner who does it in Vietnamese. When I was in a bilingual office, my main partner was a Vietnamese guy. However, we also provide instructional support by demonstrating approaches or strategies in English as a Second Language as well as bilingual lessons.

Steve: What timeframe was this?

Shannon: ‘80’s. I started teaching in 1980, I worked seven years at Franklin Elementary School [in Oakland’s Chinatown, editor] as a classroom teacher and went off to the bilingual office for five years 1987-94 something like that.

Steve: ‘87-’94 Okay, that’s a long time. What was the population of Asian students in the Oakland system?

Shannon: You know what…I never paid attention because I was so focused on the lowland, the Flatlands schools. Flatlands schools were mainly Black, Spanish-speaking, and low-income students, except for Lincoln Elementary over in Oakland Chinatown. That was the majority of Chinese students.

Steven: They called it Flatlands because…?

Shannon: The Flatlands schools are on the other side of a certain freeway where the hills start and where there are better residential areas. So between West Oakland, middle Oakland pointing toward East Oakland, that’s the Flatlands. We used to live on Wood Street, all the way down to nearly 150th in Oakland, it’s called the Flatlands.

Steve: Did you think the budget for your program was sufficient throughout this period?

Shannon: Yes, and no; but the next question is: Was it well used? Not necessarily. And the reason why is because there are definitely some people who don’t really treasure bilingual education. And so from the district level through the classroom, to the school, things were not managed very well. There’s also a challenge for those schools that don’t get bilingual funding. The bilingual funding did not only pay for some teachers, but it paid for instructional assistants, and bilingual instructional assistants. Sometimes when the budget is low, the first thing that goes are the bilingual assistants. The advantage of bilingual assistants is that they are helpful because bilingual assistants are more fluent speakers of that language, Vietnamese, some form of Chinese, or Spanish.

Steve: Could you repeat that?

Shannon: When the budget is low for bilingual education, given to the school district by the government, sometimes the first items that will be cut by the administrators will be the instructional assistants. They are valuable because they are the most fluent language speakers.

Steve: So instructional assistants are not necessarily certified teachers, in other words.

Shannon: They are not certified teachers. Okay. So I was fortunate that I had an instructional assistant who spoke more English. She happened to be a Chinese language school teacher in Oakland Chinatown. She would share certain phrases that I did not know. With Cantonese as a second language there are common daily phrases that I’ve spoken at home in [vernacular] — that is, we didn’t speak formal Cantonese. Cantonese terminology in mathematics, psychology, and social studies was foreign to me. I had to learn those words. I got so used to speaking Cantonese in a roundabout way that there could’ve been one word that meant everything I had said, but I didn’t know that word. And ironically, if I heard that word, I knew what it was. But it didn’t come to my head. So when I’m teaching sometimes, I will go around about ways to explain it to students. My instructional assistant would write the formal word on my chalkboard for me to learn. And then after class, she would go, ‘That’s the word you were trying to say!’

Steve: That’s actually very amazing.

Shannon: I had a very good instructional assistant. So it was a learning situation when I was in the classroom. My Cantonese improved because I had to use it more, not only to teach but to speak to the parents. It was a good learning curve. The second thing I think is interesting is that teaching English as a second language is not an easy format to teach.

Really, you really have to understand that in the adult ESL program, one learns thematically. You know going to school, into an occupation, or going to a grocery store, things like that the parents have to absorb because this is more of their everyday thing, right? Learning English in elementary school, in middle or high school, a student has to learn how to go to the bathroom, you know, tell other students what to do.

So teaching English to students from immigrant backgrounds must also relate to the end-of-year tests that are held in English. Right? We have the end-of-the-year tests right? It’s the standard English test that everybody has to take. That tells you how much learning you have retained, not necessarily how much English fluency you have.

So we have, you know, we have American English-speaking students in our schools. We have a handful of fluent English speakers with a Latin surname. So they have greater success with English due to exposure in everyday life. The bilingual kids — the Cantonese, Spanish bilingual, or Vietnamese bilingual kids, they have their parallel experiences compared to the already established English speakers. And the thing was, our English speakers are not high up there. They don’t score perfect A’s, they don’t score 100%. Their English is not that good. Their English only met certain standards.

But the bilingual kids scored worse than that. Of course, our challenge was teaching them not only English as a second language orally. Let’s transfer it into a reading where they could read and pass certain tests. And here comes another obstacle, there’s also unfamiliar English vocabulary.

There are totally different layers of an onion that you have to peel off to get them to be successful. For people like me, when I was a teacher trainer, it’s not just that I couldn’t speak fluent English, but my thinking was still in Chinese. So I still reversed my sentence structure.

Steve: You thought in Chinese?

Shannon: I didn’t know that. It was because of our language. Our first language was in Toisan, right? And so my thinking is like I still spoke in Toisan, like instead of ‘where are you going?’ It was ‘You are going where?’

So when I taught English as a second language I also learned to improve my own English speaking patterns. So as I trained teachers who taught in the classroom, my English actually improved. My writing improved and my Cantonese improved.

Steve: That’s fascinating.

Shannon: However, my Chinese probably does not surpass the 3rd-grade level from Hong Kong or China.

End of Part 1.

Notes.

1 From Wikipedia: “Sheltered instruction is an educational approach designed to make academic content more accessible to English language learners (ELLs) while promoting their language development. It involves modifying instruction to accommodate students’ language proficiency levels and providing additional support to help comprehend and engage with material effectively.”

2 See Footnote #1

3 From Wikipedia: Lau vs Nichols “case in which the U.S. Supreme Court on January 21, 1974, ruled (9–0) that, under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a California school district receiving federal funds must provide non-English-speaking students with instruction in the English language to ensure that they receive an equal education.”